At day camp, we didn’t have a campfire, so we told ghost stories on the racquetball courts. (My camp happened to convene at a health club.) The courts’ lights were powered by sensors, and we thought it was the coolest thing in the world to keep still long enough that the lights would go out and we’d be in the dark. And that’s when someone would start telling the story of the guy with the hook or the car that kept flashing its lights at other cars, which would eventually lead to gasping and screaming, which would eventually lead to the lights flashing back on.

The point is, even we, the wussy day campers who couldn’t handle being outdoors or away from our families for too long, told ghost stories. Because camp and ghost stories just went together.

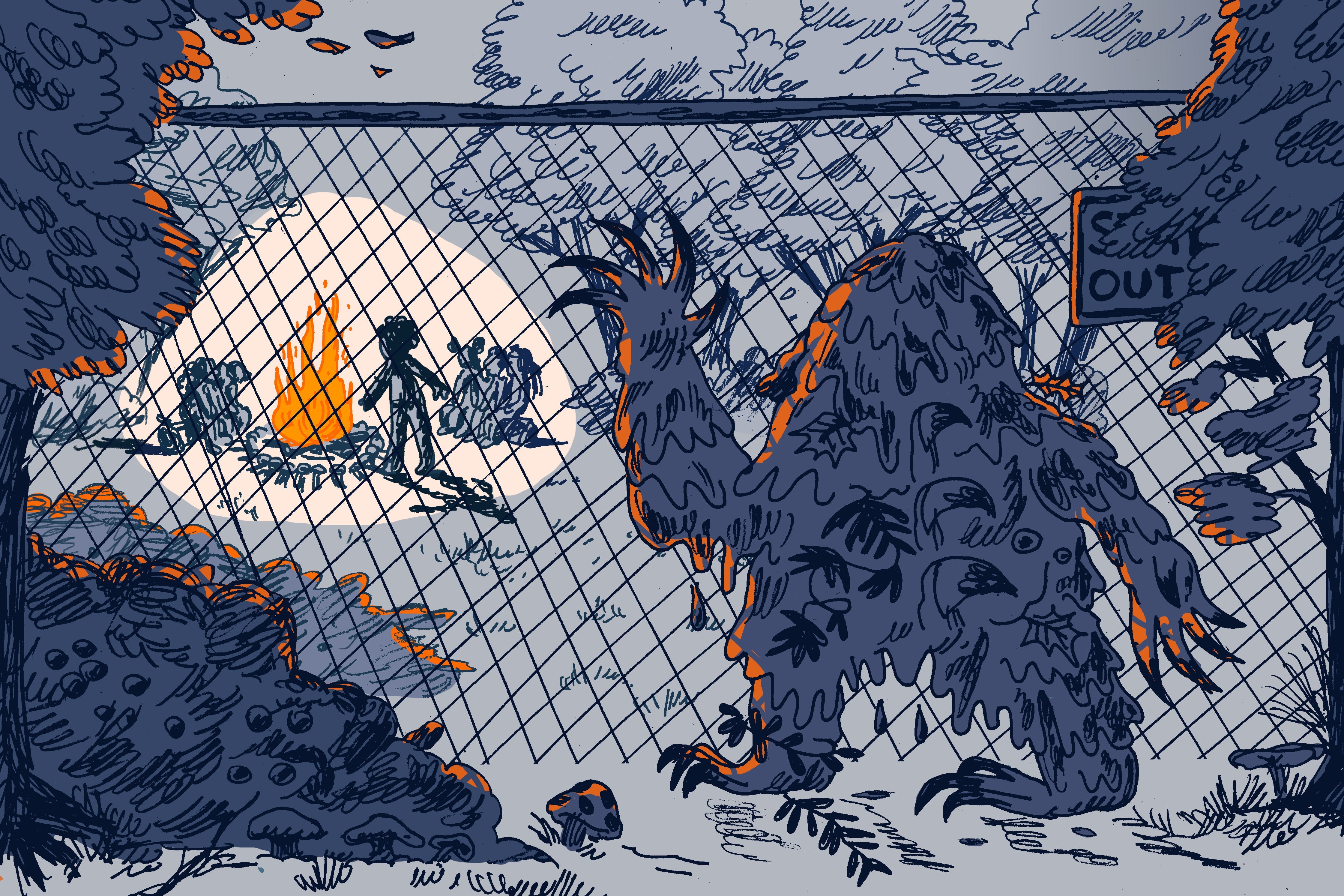

They used to, at least. The tradition of gathering around the campfire to tell scary stories, I recently learned, seems to be increasingly rare at American summer camps.

“I think most camps are moving away from the scary story idea, much in the way that camps are moving away from pranks,” said Kurt R. Podeszwa, director of Camp for All, a Texas camp for children with challenging illnesses or special needs. Nowadays, “most camps are really focusing on youth development,” he said.

A similar rule governs Camp IHC in northeastern Pennsylvania. “Now we talk to our staff about not telling ghost stories or scary stories at bedtime,” said Lauren Rutkowski, the camp’s owner and director. For young kids, “bedtime’s the time that we talk about good things, and upbeat things, and things that we’re excited for the next day.”

A few years ago, a Boston Globe columnist noticed—and lamented—the fading away of the camp ghost story tradition. At least one recent major movie seems to share his affection for a good adolescent scare. “Isn’t conquering fear an integral part of growing up?” he asked.

Not where today’s parents are concerned. “Parents have way more anxiety sending their kids to camp than kids do [going],” said Jon McLaren, executive director of YMCA Camp Minikani in Wisconsin. “They picture their pride and joy, their sweet thing scared around a campfire. That’s just unacceptable.” For parents, in fact, scary stories and anxiety might be one in the same.

Traditionalists will be pleased to know that scary stories have not died out completely. At Camp IHC, for example, the kids are allowed to tell them among themselves—in daylight. “I think that the way the kids do it now is a little bit different from how I did it when I was little,” Rutkowski said. “Ghost stories were something that we told at bedtime or around the campfire when it was dark. I don’t think that’s really how it plays out now. I think the kids today talk about it all through the day.” (She added, “Looking at it from an adult’s eyes, it’s precious, because you see these little kids with their eyes bright and beady listening to these stories, and then they come up to me for clarification: ‘Was there a camper called Cropsey? What do you mean it’s a story? Why would they make that up?’ ”)

Come to think of it, I’m not sure it was counselors at my camp telling these stories on the racquetball courts so much as fellow campers. But there certainly were camps where counselors did the scaring themselves: According to historian Leslie Paris, who wrote a book about the history of summer camp, in the 1960s, folklorists started studying and recording the culture of summer camp, including the tradition of ghost stories. Researchers surmised that the stories functioned as a way to build community—and for counselors to establish authority over campers. “There’s a message in those stories which is that ‘it’s scary out in the woods at night,’ ” Paris said. “If you leave your cabin in the middle of the night and go wandering, it’s a little bit scary.”

McLaren was a camper at Minikani, the camp he now oversees, in the 1980s and remembers the heyday of scary stories. “When I was a camper, absolutely we had scary stories,” he said. “I was petrified and couldn’t go to sleep. We had the Mud Lake Monster, and we had Grandpappy.”

Larry Wilensky, the “resident storyteller” at Camp Iroquois Springs in Rock Hill, New York, remembers the experience as more pleasant, less terrifying. He wrote in an email, “I have wonderful memories of being a camper in the early 1970s getting to hear the wonderful camp storytellers of that era recount ‘The Tell Tale Heart’ and ‘The Masque of the Red Death.’ ”

McLaren has a more sinister recollection: “Somewhere along the line, counselors went rogue and it turned into, ‘What do we do to scare these kids?’ ”

It’s not uncommon for camps to have their own camp-specific stories and legends, the way Minikani has the Mud Lake Monster and Grandpappy and IHC has something named Cropsey. “At our camp, we have this legend called ‘Cropsey’ that the kids have been talking about for years,” Rutkowski explained. “Every year, the story evolves and changes, about this camper that went to camp and his name was Cropsey. There are so many versions of the story, that he maybe got lost in a lake or he got lost in the woods.”

Rutkowski said she wouldn’t want to do away with Cropsey completely. “Look, we could try our best to say nobody’s ever allowed to talk about any of this stuff, but those are the moments that kids love, because they’re talking about things that they know they shouldn’t be talking about,” she said.

McLaren felt similarly. He said he has “sort of brought back” what he calls legends and lores, “but we’re not really calling them scary stories.”

“I think it’s neat and important to be sitting around a campfire and to hear an interesting story, so we’re teaching the art of storytelling to really just engage the campers and maybe get ’em a little, ‘Oh, what was that sound in the woods?’ But the goal is not to scare anymore,” McLaren said. Counselors are instructed to adapt any stories they share to make them age-appropriate: “Just a little spooky for 8-year-olds and then really scary for the teens.”

Wilensky added that the campfire tradition, too, has evolved. “Storytelling is a less-frequent part than it used to be—campfires now tend more toward singalongs, camaraderie, and games.” Podeszwa agreed: “For us, our traditions around campfires are more around singing as well as telling accomplishment stories around the campfire, things people feel good about that day.”

And some camp directors just aren’t the scary story type. “We really focus on goals and outcomes, measurable things that can be achieved at camp and, really, especially focused on youth development,” Podeszwa said. “How are we developing the youth that comes to our camp for the future?” Tell that to Cropsey and Grandpappy.