Early in Aquaman, the first big-screen solo adventure for DC Comics’ long-running undersea superhero, a battle breaks out in the home of lighthouse keeper Thomas Curry (Temuera Morrison). It’s a chaotic struggle between Atlanna (Nicole Kidman), a princess of Atlantis, and those trying to force her to return home against her will. Her heart belongs to Thomas and their young child, Arthur, but tradition and history have other plans for her, and ultimately pull her away from her family to some unknown fate back in the world of her birth—a place with clearly defined notions of who belongs where and who should associate with whom. (Well, eventually the movie reveals that fate, but let’s call it unknown for now, for the sake of spoilers.)

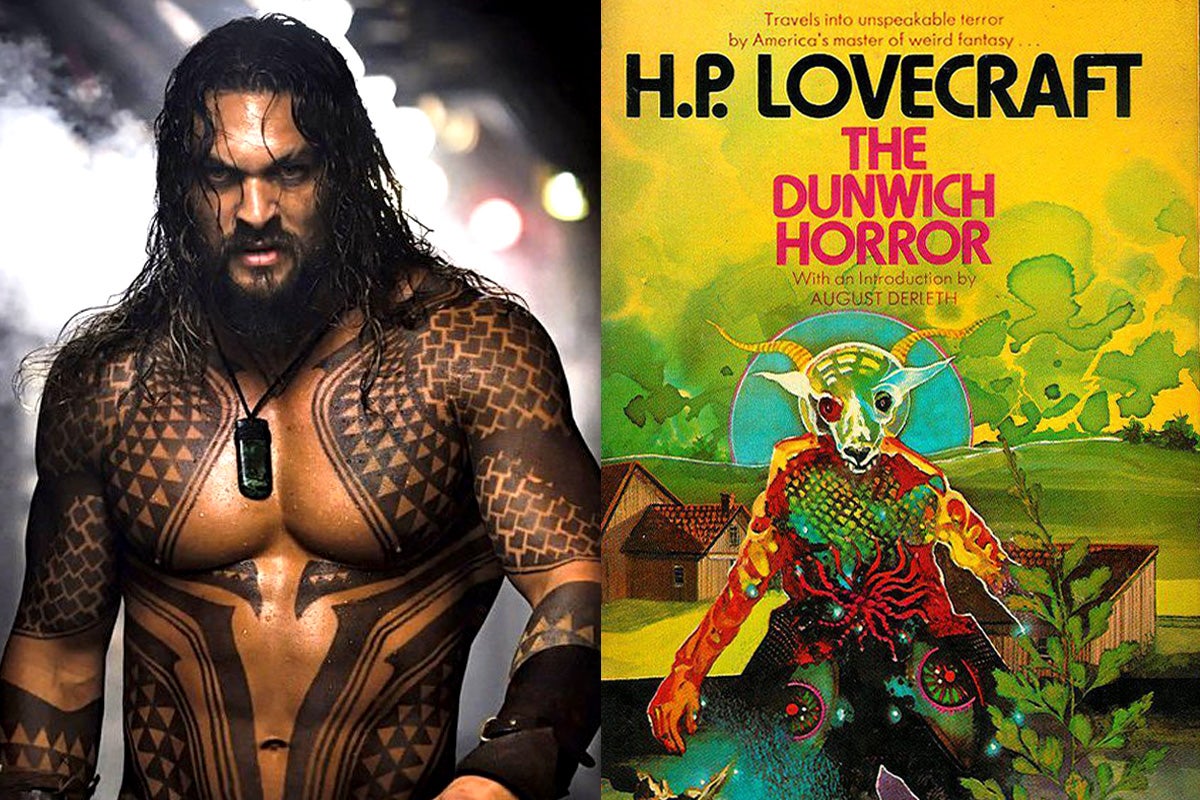

But prior to the attack, it seems that either Atlanna or Thomas have been doing some reading. Despite the chaos, director James Wan lets the camera hold a moment on a coffee table whose contents include a paperback collection of H.P. Lovecraft stories named after one of his most famous tales, “The Dunwich Horror.” This isn’t a tossed-off detail. It’s a nod to how much the film owes to Lovecraft, who set his stories in a world filled with lost civilizations, colossal beings of unknowable age and unspeakable powers, and the couplings and resulting offspring of humans and beings from other worlds, all of which find their way into the film. Lovecraft’s influence is all over Aquaman. It’s also a film that would have repulsed him.

Then again, a lot of things repulsed Lovecraft, and nothing more than that which he couldn’t understand. Or as Lovecraft himself put it in his literary survey, “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” For Lovecraft, that included then-recent scientific discoveries in astronomy and biology that shed light on the full scope of time and space and dwarfed humanity’s place in the cosmos, making us seem like little more than mites in the grand scope of the universe.

Lovecraft’s fear took other forms, too. He was deeply racist in ways that go even beyond being the product of his time. Lovecraft was born in Providence, Rhode Island, and mostly stayed there apart from a two-year sojourn in New York between 1924 and 1926. That stint began with him enthusiastically befriending others in the literary world and ended with the impoverished writer fleeing the city, driven away in part by his hatred of the “hybrid squalor” created by immigrants. Lovecraft’s wife Sonia Greene describes watching him being driven into a rage at the mere sight of minorities and says he explained his behavior thusly: “It is more important to know what to hate than it is to know what to love.” (That Greene was Jewish was also apparently a source of tension in their marriage, which lasted on paper much longer than their co-habitation.)

But while it’s accurate to call Lovecraft more racist than most others of his background, it’s not fair to treat him as an anomaly. “It is possible to perceive Howard Lovecraft as an almost unbearably sensitive barometer of American dread,” Alan Moore wrote in his introduction to The New Annotated H.P. Lovecraft, continuing, “Far from outlandish eccentricities, the fears that generated Lovecraft’s stories and opinions were precisely those of the white, middle-class, heterosexual, Protestant-descended males who were most threatened by the shifting power relationships and values of the modern world.” Lovecraft, in other words, just had a habit of saying the quiet part out loud.

Lovecraft’s racism found its way into his correspondence in explicit, uncensored form. It was usually a bit more coded in his literary work. Usually. Lovecraft sometimes went beyond the racial stereotypes endemic to the pulp magazine world in which he published. He wrote some grotesquely racist poetry, and his feelings of repulsion toward immigrants and their ways are close to the surface in stories like “The Horror at Red Hook.” More often, however, he filled his stories with images of degeneration and decay in line with his views on racial purity. There’s a bit of that in “The Dunwich Horror.” In that 1929 story, Aquaman’s Atlantean mom and human dad would have read about the monstrous offspring of a deformed woman and an otherworldly being as they settled into a culture-bridging marriage and raised a child born of two worlds.

Even more relevant is Lovecraft’s 1936 story “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” in which a visitor to the Massachusetts town of Innsmouth uncovers an arrangement with an undersea race of “Deep Ones” who have mated with locals, leading its residents to take on fishlike features.

It’s a story not-so-subtly inspired by Lovecraft’s horror at miscegenation. It’s also one of Lovecraft’s most memorable. And that’s the paradox of Lovecraft: How do you reconcile the power of his imagination, the richness of the worlds he created, and the influence he’s had on horror and science fiction writers ever since with the racist foundation on which all that is built? For some, that’s meant shoving Lovecraft into the shadows. In 2015, the World Fantasy Awards abandoned its old trophy design, a bust of Lovecraft, in favor of the less controversial image of a tree and moon. For others it’s meant putting their own anti-racist spin on Lovecraft’s work.

Aquaman falls squarely into the latter camp. Where Lovecraft saw the offspring of two societies as a sign of decay, the film positions Aquaman, born Arthur Curry (Jason Momoa), as a character whose background makes him uniquely qualified to both heal the rifts in the undersea kingdom and end the battle between the worlds of land and sea. His mixed-race background isn’t a curse, as Lovecraft would no doubt have seen it, but a blessing.

Like the placement of that Lovecraft paperback, this is no accident, nor is the casting of Momoa, an actor of Native Hawaiian, German, Irish, and Native American descent. After seeing the film, Walter Chaw, a critic for Film Freak Central, tweeted, “In Aquaman, the hero is the product of Asian/Caucasian miscegenation, played by an actor of mixed Native Hawaiian heritage. My kids are mixed in exactly the same way. Even if the film wasn’t great, I would have loved it just for doing this.” Wan replied, “Arthur’s the very definition of biracial. Half Surface Dweller, Half Atlantean. Momoa’s mixed heritage perfectly aligns with this. As the world becomes increasingly diversified/mixed, it’s great to have a character modern kids can identify with. This was an important msg for us.”

That it’s the exact opposite of the sort of message Lovecraft tried to send, and one delivered using the devices he created, is the sort of twist even he couldn’t have imagined in his darkest dreams.